19.10.2022Brushing Against the Grain of History:

Mathieu Buchler

Brushing Against the Grain of History:

Lora Webb Nichols’

(Scarred) Negatives

Mathieu Buchler

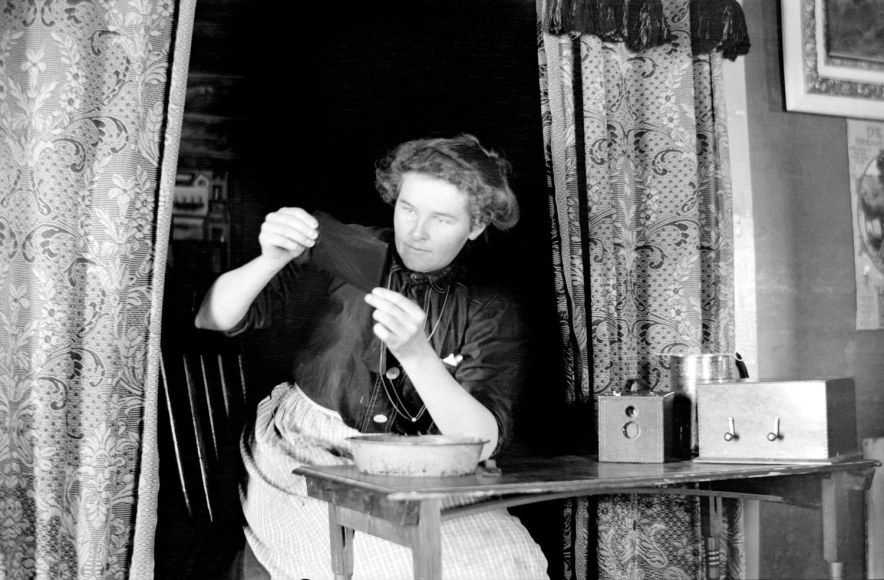

Lora Webb Nichols, 1909

The Lora Webb Nichols Archive, assisted by photographer Nicole Jean Hill and Nichols family-friend Nancy Anderson, recently published Encampment, Wyoming (Fw: Books, 2022), a collection of 115 pictures selected from the more than 24.000 negatives left behind by pioneer photographer Lora Webb Nichols (1883-1962). [1] Constructed as an opening into the mesmerising work of Nichols, the book suggests that an archive of pictures conserved originally for their historical significance, depicting life during the sharp rise and decline of Wyoming’s copper mining industry, may harbour a vivid body of work worth excavating. Yet, the archived negatives themselves also tell their own, less apparent, history. Showing traces of handling and damage, they serve as a spectral reminder, through the altered topography of the emulsion layers, how in photography image and history converge on the negative’s changing material plain, raising the question of whether the degradation of negatives over time may be integral to the pictures they hold within.

Encampment, Wyoming is evidently more than a piece of historical documentation. Flipping through its pages, one is met with a surprising sequence of dynamic photographs: a portrait of a woman arching her body forward and letting her hair hang parallel to her legs; a still life of a vase of sweet peas placed in front of a makeshift white backdrop awkwardly set up on a dining table; a portrait of a foal leaning against a wooden house and scratching its front leg with Nichols’ own shadowy silhouette spanning across the grass in the lower third of the image. The book serves as a testimony to a female visionary’s interpretation of the medium as an open encounter between an evolving rural landscape and an observant photographer. Embedded deep within the pictures lies a mnemonic for a lived present long past, in which Nichols’ authorial presence is still strikingly apparent.

What is particularly intriguing is that Nichols’ presence is at the same time directly material. Nichols handled her negatives herself, and partially made a living developing films and making prints at her own commercial darkroom, The Rocky Mountain Studio. She was deeply immersed in the physical and mercantile aspect of photography, making the negative a crucial component of her personal interaction with the medium. As Nichols writes in a cathartic poem about the process of printmaking scribbled down in one of her notebooks after a long, frustratingly laborious day in the lab, with her children sick and her husband out of work: “In the heart of that magic picture I ride // Alone …… with the memory of you.”

Nichols poured herself into her photographic practice, and left her traces on the negatives. Most frames show subtle signs of deterioration, with many of them lightly scratched, punctured or otherwise damaged. One particular archival scan labelled Mabel Wilcox and pup “Button”, depicting a girl on a front porch ordering her dog to sit, shows a dark curve next to the girl’s head, possibly due to a nick caused during development, and numerous smaller scratches and specks of dust all over the surface. The book print retains the shadowy curve, yet the remaining imperfections have been digitally brushed over. Curiously, in an article by Sarah Blackwood for the New Yorker, the dark line, too, was digitally removed, with traces of it still visible upon close inspection. [2]

Encampment, Wyoming is evidently more than a piece of historical documentation. Flipping through its pages, one is met with a surprising sequence of dynamic photographs: a portrait of a woman arching her body forward and letting her hair hang parallel to her legs; a still life of a vase of sweet peas placed in front of a makeshift white backdrop awkwardly set up on a dining table; a portrait of a foal leaning against a wooden house and scratching its front leg with Nichols’ own shadowy silhouette spanning across the grass in the lower third of the image. The book serves as a testimony to a female visionary’s interpretation of the medium as an open encounter between an evolving rural landscape and an observant photographer. Embedded deep within the pictures lies a mnemonic for a lived present long past, in which Nichols’ authorial presence is still strikingly apparent.

What is particularly intriguing is that Nichols’ presence is at the same time directly material. Nichols handled her negatives herself, and partially made a living developing films and making prints at her own commercial darkroom, The Rocky Mountain Studio. She was deeply immersed in the physical and mercantile aspect of photography, making the negative a crucial component of her personal interaction with the medium. As Nichols writes in a cathartic poem about the process of printmaking scribbled down in one of her notebooks after a long, frustratingly laborious day in the lab, with her children sick and her husband out of work: “In the heart of that magic picture I ride // Alone …… with the memory of you.”

Nichols poured herself into her photographic practice, and left her traces on the negatives. Most frames show subtle signs of deterioration, with many of them lightly scratched, punctured or otherwise damaged. One particular archival scan labelled Mabel Wilcox and pup “Button”, depicting a girl on a front porch ordering her dog to sit, shows a dark curve next to the girl’s head, possibly due to a nick caused during development, and numerous smaller scratches and specks of dust all over the surface. The book print retains the shadowy curve, yet the remaining imperfections have been digitally brushed over. Curiously, in an article by Sarah Blackwood for the New Yorker, the dark line, too, was digitally removed, with traces of it still visible upon close inspection. [2]

Lora Webb Nichols, Mabel Wilcox and Pup “Button”, 1902, 2000, 2022

Left: Archival Scan, Middle: Book Print, Right: New Yorker Edit

Left: Archival Scan, Middle: Book Print, Right: New Yorker Edit

While digital restoration is by now standard, and welcome, practice in making century-old film strips produce clear pictures, it might be worth considering whether there is a semantic weight to the imperfections found on Nichols’ negatives. Not only are they traces of her manual interaction with her photographic work, they are also marks caused by many years of personal appreciation and, later, attempts at conservation. With fingers, sleeves and negative holders having brushed against their grainy surface over decades, Nichols’ scarred negatives are a monument to photography’s inherent temporality and material history. Carved onto the silver plain, these scars trace, like a hair-thin scratch, a historical line between 20th-century Encampment and today’s viewers. As such, they may have become integral to the world which Lora Webb Nichols created with such a singular gaze.︎

Mathieu Buchler, co-founder of Mnemozine, studied philosophy at University College Dublin and at Freie Universität Berlin. He currently works as a writer, translator, editor, photographer and teacher.

You can find more of his work here on Mnemozine, on his website mathieubuchler.com or on Instagram @mathieu.buchler.

[1] Nichols, L.W. Encampment, Wyoming. Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948. Nicole Jean Hill (Ed.). Amsterdam: Fw:Books, 2022.

[2] Blackwood, S. “A Woman’s Intimate Record of Wyoming in the Early Twentieth Century”. New Yorker. July 28, 2021.

Mathieu Buchler, co-founder of Mnemozine, studied philosophy at University College Dublin and at Freie Universität Berlin. He currently works as a writer, translator, editor, photographer and teacher.

You can find more of his work here on Mnemozine, on his website mathieubuchler.com or on Instagram @mathieu.buchler.

[1] Nichols, L.W. Encampment, Wyoming. Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948. Nicole Jean Hill (Ed.). Amsterdam: Fw:Books, 2022.

[2] Blackwood, S. “A Woman’s Intimate Record of Wyoming in the Early Twentieth Century”. New Yorker. July 28, 2021.